Like any hobby, scale modeling has some safety considerations that you should be aware of. Fortunately, the learning curve correlates with the danger level: that is, new modelers are generally working around fewer hazards than people who have been in the hobby long enough to want to advance their skills. This page discusses some of the potential hazards that you should address.

Sharps

The first (and probably most critical) tool most modelers encounter is the simple hobby knife. We use it for removing shrinkwrap, opening parts bags, cutting tape, removing parts from sprues, making simple corrections and modifications, opening panels, and carving all-new parts when needed. When new, these blades are often sharper than most other blades you'll find around the house, and as such they deserve a little extra respect when you're handling them. Remember the standard knife rules:

- Always cut away from yourself

- Never use a dull blade for cutting

- Always use the right knife for the job

Pretty standard, right? Let's break it down a little further so that we can see how these relate directly to modeling

"If you cut away from yourself, you'll never get cut" is a tried-and-true saying that probably dates back to the sharpened rock being used to make a pointed stick. Start with this general safety precaution, and let your personal style develop naturally as you get used to working with the knife. Whatever you do, don't try to copy the style of someone more experienced: they've had years of making their own scars and calluses, and trying it their way out of the gate may lead to a trip to the doctor to get some stitches.

"Never use a dull blade for cutting" is especially true in modeling. Not only will you risk ruining whatever you're working on by sending a wayward blade through the middle of a part, dull blades can be physically dangerous. When you try to use a dull blade to make a cut, you have to put more force behind it to do the job. More force = less control = greater likelihood of a blade changing direction and cutting you. Hobby blades are also often made of a hardened metal that tends to shatter rather than bend if too much force is placed on it. Yes, you may be setting yourself up for knife shrapnel if you don't follow this simple precaution. Considering how cheap and easy it is to get replacement blades, you should always have a supply of spare blades on hand for whenever the one in the knife starts to get dull. And please, do everyone a favor: don't toss bare blades in the trash. Just because they're too dull to use at the workbench doesn't mean that they're too dull to go through a garbage bag. Put them in a solid container of some sort: a hard plastic bottle or metal container works well.

Last but not least, make sure you always use the right knife for the job. If you're trying to cut .080" sheet styrene by forcing your way straight down through the face, you're going to be very disappointed (if not injured). Hobby knives work best for cutting through thin cross-sections. If you're trying to cut through a wide but shallow cross section, use multiple swipes to cut through the plastic as if the knife blade was a single saw tooth. If you're trying to cut through a wide and thick piece of plastic, don't even waste your time with the knife: use a saw.

Knifes aren't the only sharps you need to be aware of, though. Plastic corners can be sharper than you think, metal axles can stab you if you're not paying attention while mounting wheels, drill bits can go through plastic and into flesh with little effort, and small cutters and scissors like to get too close to fingers just before you bring the blades together. All of these can be prevented with a little common sense: don't rush, pay attention to exactly what you're doing when you're doing it, and if something doesn't fit don't force it bare-handed. Metal axles can be driven home with a small block of wood and a few light hammer taps...there's no need to be leaning over a table putting all of your weight onto the top wheel and trying to stab yourself in the chest when that wheel slips off to one side.

Glues & Chemicals

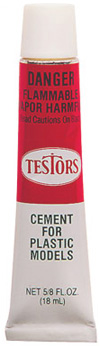

The next most common toll on the workbench is glue. Without it, we're pretty much limited to snap-together models. Glues are often a concern for parents who have heard the claims of rampant huffing and fear for their child's well being. Fumes pose a valid risk and we'll get to that in the next section, but for now I want to mention the physical aspects of glue and other chemicals.

The short version is: don't get anything on you.

More realistically, some chemicals are safer than others. Acrylic paints and non-toxic glues should be used by new modelers to allow them to get used to how to work with this aspect of the hobby. Water-based paints are easy to clean up and, although not ingestible, pose little to no safety risk if they get on your skin. Good old Elmer's white Glue is a staple for many modelers, and is pretty much as safe as you can get.

When you're ready to move on to more heavy-duty chemicals, you'll also have to step up your precautions. Super glue - aka cyanoacrylate - can bond skin instantly, so if you have that on your bench make sure to have a bottle of nail polish remover nearby as well (simply pulling your glued-together fingers apart and ripping off bits of your own skin isn't nearly as much fun as it sounds). Avoid skin contact with any glues and paint not labeled "non toxic," as they may contain metals and other chemicals that can be absorbed through your skin.

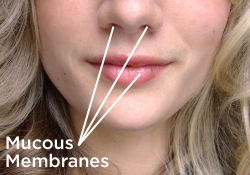

Speaking of metals, you may see many modelers (myself included) who use lead in their projects. Lead is a wonderful material that's inexpensive, easy to shape, retains its new form with no effort, looks good when installed, and can be drilled, glued, and generally worked with effortlessly. It's also a fairly toxic material that can cause a host of problems if you are overexposed to it (see OSHA's page on the subject). If you want to work with lead (or similar materials), go for it: just take some basic precautions as well. Wear gloves, wash your hands, and don't touch your face with the metal or your hands while you're working. Basically, you want to avoid prolonged skin contact and all mucous membrane contact.

If you want to try you hand at modifying diecast cars, you may hear tell of hobbyists using "Aircraft Stripper" to remove the factory applied paint. Like lead, its usefulness is counterbalanced by its threat. It will literally pop the paint off metal within seconds, and if you get it on you it can cause a nasty chemical burn in about the same time. Wear goggles, gloves, and take whatever safety precautions you can to make sure it doesn't get on you. This is generally true of all paint strippers and de-greasers (often used for cleaning parts and paint).

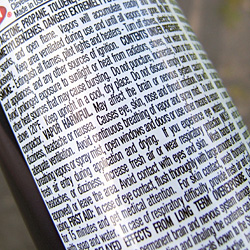

Fumes

This is probably the most hazardous part of our hobby. Model builders work with a number of substances that range from relatively harmless to lethal. In the above section, I mentioned the concern some parents have about huffing. It's not a new danger (Lloyd Bridges made his famous "sniffing glue" joke over a quarter century ago), but paint and glue fumes can pose a real threat. If you're a parent concerned about legitimate use of these products, don't discourage the hobby: instead, recommend a couple of snap-together kits or purchase fume-free products for your new modelers. Once you see they're serious about the hobby and are responsible with their tools, more advanced building materials may become appropriate. Just make sure all of these products - whether they are being used by yourself or someone else - are used in a well-ventilated area. Rod Stewart is known for working on his model railroad in hotels while touring, and would always work near an open window regardless of the outside temperature to make sure he wasn't turning the room into a fume cell.

Once you start using spray paint (either rattle cans or an airbrush), the absolute best investment you can make is a paint booth. It can be purchased or built at home for very little cost, and will help remove fumes from the area, protect your new paint job from dust, and make laying out newspapers and cleaning up accidental overspray a thing of the past. If you decide to build your own, be sure to use a fan with a sealed or remote motor - if the motor is in the air flow, it will get gummed up with paint and can pose a fire hazard. That's right - these fumes aren't only dangerous to inhale, they're flammable. So no smoking, no candles, and no sparks anywhere near where you're painting.

After you have a paint booth, you should also consider a respirator. Not a dust mask: those are good for when you're sanding, but useless for paint and solvent fumes. If you're going to get something, get a real respirator and extra filters for it.

If your modeling progresses to the point of making and casting your own parts, you'll have the honor of working with one of the nastiest fume-producers around: two-part resin. Industrial styrene casting is done by heating the styrene until it is a liquid and injecting it into a mold. Since most of us don't have the money needed for that kind of equipment, we turn to two-part resin. Instead of being heated, this resin is shipped to us as two separate bottles of liquid that need to be mixed together in an exact ratio and poured into a mold where it will chemically change into a solid. Both of these raw liquids produce fumes that can cause nausea, dizziness, and neurological problems, and these fumes only get intensified when the two are mixed and the combination process starts. The resulting plastic is no more harmful than any other model part, but the process to get there has caused many modelers to get very ill over the years.

Motor Tools

"Motor tools" is a simple catch-all to describe lathes, drills, Dremels, saws, sanders, and more. Even though these are all very different tools, they share a few common risks that you should be aware of if you want to use them. All of these tools have spinning motors that can easily snag on loose clothing and hair, so make sure you tie back or remove anything you don't want accidentally sucked into the motor. Even the relatively small Dremel can give you a really bad day if you're not careful. A low-speed Dremel spins at about 5,000 RPM - if you luck out and get your hair caught around a thin shaft (say, 0.5"/1.25cm circumference), it's still going to wrap nearly two feet (50cm) of that hair around itself in the first half-second. Also, wear eye protection. It takes you about .3 seconds to blink, and it takes slightly less time for a piece of sharp plastic or metal to travel between your hands and your face. If you don't happen to be working with your arms stretched out, you'll have even less time. Lastly, wear a dust mask if you're going to be sanding. Even if you're sanding a relatively harmless material, the dust can still be an irritant.

Even the relatively small Dremel can give you a really bad day if you're not careful. A low-speed Dremel spins at about 5,000 RPM - if you luck out and get your hair caught around a thin shaft (say, 0.5"/1.25cm circumference), it's still going to wrap nearly two feet (50cm) of that hair around itself in the first half-second. Also, wear eye protection. It takes you about .3 seconds to blink, and it takes slightly less time for a piece of sharp plastic or metal to travel between your hands and your face. If you don't happen to be working with your arms stretched out, you'll have even less time. Lastly, wear a dust mask if you're going to be sanding. Even if you're sanding a relatively harmless material, the dust can still be an irritant.

So there you have it: your crash course in modeling safety for the most common hazards in the work shop. Most of this should be pretty straightforward: tools should be in good working order and used appropriately; be awake, alert, and aware of your surroundings and focus at all times; paints, glues, and plastics are for enhancing the model, not you. If you follow these steps, you can still enjoy the hobby without risking yourself. Remember: if you think it's a pain to take some precautions now, just think of how much worse it will be after the accident.